Timeless Perspective on Investing in Anything

From shares in companies, to places we choose to live, people we spend time with, and careers we dedicate ourselves to.... Who reaps the majority of the reward?

To invest:

verb

gerund or present participle: investing

put (money) into financial schemes, shares, property, or a commercial venture with the expectation of achieving a profit.

devote (one's time, effort, or energy) to a particular undertaking with the expectation of a worthwhile result

In the early 1900s, a famed stock investor by the name of Jesse Livermore was the protagonist of a book, written by journalist Edwin Lefèvre, called Reminiscences of a Stock Operator. Even though it was published over 100 years ago in what were then the nascent early years of financial markets, the book is generally considered a bible of sorts for investors to this day because its lessons and virtues have stood the test of time. The quote on the second page of the book, “There is nothing new in Wall Street,” or better yet the expression by King Solomon about 5,000 years ago when, in the Book of Ecclesiastes, he wrote, “There is nothing new beneath the sun,” aptly brings this point into focus.

Once we touch upon a fabric that seems to emerge from a timeless thread, it’s patterns and principles weave themselves into the contemporary modes of how life functions. And when it comes to the investments we make in our lives, what makes one decide to commit the next decade of their life to living in a particular place? How come one marriage is abundant in togetherness, growth and health, even behind the curtain, while another is fraught with insecurity, resistance and a constant urge to separation? As we grow, we all develop internal filters which attempt to determine a meaningful harmony between our positive inner needs and desires, and what the environment outside of us is capable and willing to offer. Yet, certain people seem to have access to these timeless threads, and they leverage them into successful major commitments they make through their lives. They don’t always get it right, but the good investments they do make, they grow into something bigger than themselves.

In Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, we bear witness to Livermore as he goes through both the pains of loss and jubilation of great successes. In the process, he evolves as an investor, and so does his capacity for reflection on what works sustainably and what is more or less whimsical. He is aptly searching for those timeless threads of good investing. One passage in the book illustrates particularly well one of the central challenges, maybe the central challenge, to good investing. Quoted below:

And right here let me say one thing: After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It always was my sitting.

Got that? My sitting tight!

It is no trick at all to be right on the market. You always find lots of early bulls in bull markets and early bears in bear markets. I've known many men who were right at exactly the right time, and began buying or selling stocks when prices were at the very level which should show the greatest profit. And their experience invariably matched mine-that is, they made no real money out of it.

Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon. I found it one of the hardest things to learn. But it is only after a stock operator has firmly grasped this that he can make big money. It is literally true that millions come easier to a trader after he knows how to trade than hundreds did in the days of his ignorance.

The reason is that a man may see straight and clearly and yet become impatient or doubtful when the market takes its time about doing as he figured it must do. That is why so many men in Wall Street, who are not at all in the sucker class, not even in the third grade, nevertheless lose money. The market does not beat them. They beat themselves, because though they have brains they cannot sit tight.

Old Turkey was dead right in doing and saying what he did. He had not only the courage of his convictions but the intelligent patience to sit tightWhat Livermore is talking about here is that many people can be right on choosing a good stock, even if only by chance, yet it is exceedingly rare to find someone with the courage to make a meaningful investment and the patience and fortitude to stick with it. Once he learned this, the millions came easier than the hundreds did in his ignorance. The value seems to come from letting a good trend accrue over time.

Is this analogous to everyday life? Below is an attempt to generalise the phrase into its primary components:

Find a way to hold on

Once you make a good choice or are blessed with a good opportunity, with the courage of your conviction, get on board, stay open and adapt however you can, and keep it going.

The main battle to success is fought within

It is the daily psychological warfare of doubt and impatience, fear and greed, and yearning for action, inaction or distraction, and a host of other characteristics which trigger us away from both letting and making life happen for us.

Let’s set the foundation now by easing our way into a closer look at the value of what he writes about in the stock investing world, by focusing on one of the most foundational companies of our generation, Apple.

Apple Computer

We all likely know about Apple today. Their computers, and then iPods, and then iPhones and iPads and iWatches, their perfectly designed boxes and clean white cables have found themselves in the homes and offices of most people in the developed world. It wasn’t always the case. Founded in 1976, infamously out of a garage in California, Apple was started by a child-like hippy, Steve Jobs, and a child-like geek, Steve Wozniak. Its first product was an assembled circuit board, without a keyboard or screen, and a plastic cover as optional - the Apple I.

Could anyone have envisioned what was to come next?

Investing in the First Wave

By 1980, it had started to become “a thing”. So much so that the big-wigs of Wall Street were bidding over who would list the company publicly on the stock market. And in December 1980, Apple became a public company that anyone with a brokerage account could invest in.

Now, imagine, before Apple became visible to the wider public: who would have owned their shares?

To own its shares you would have had to be in the right place, at the right time - either as an early employee or founder, or as a venture capital angel investor. That meant living somewhere nearby to Los Altos, California (Steve Jobs’ garage). It also probably meant being a geek of some sorts with an interest in computers. If you had those two filters met, your luck would have been at least somewhat provoked. Mike Markkula was one of those people who gave the two founders about $100,000 in investment funds and provided managerial support, and ended up owning 26% of the company’s shares at its incorporation (the same amount as the two Steves).

When Apple went public in December 1980, the founding shareholders became very wealthy. Its initial market value was $1.8 billion, so even a small percentage of ownership in shares would have meant a large sum of money. A good investment.

And now, anyone in the world would be able to invest in Apple, both through its highs… and lows.

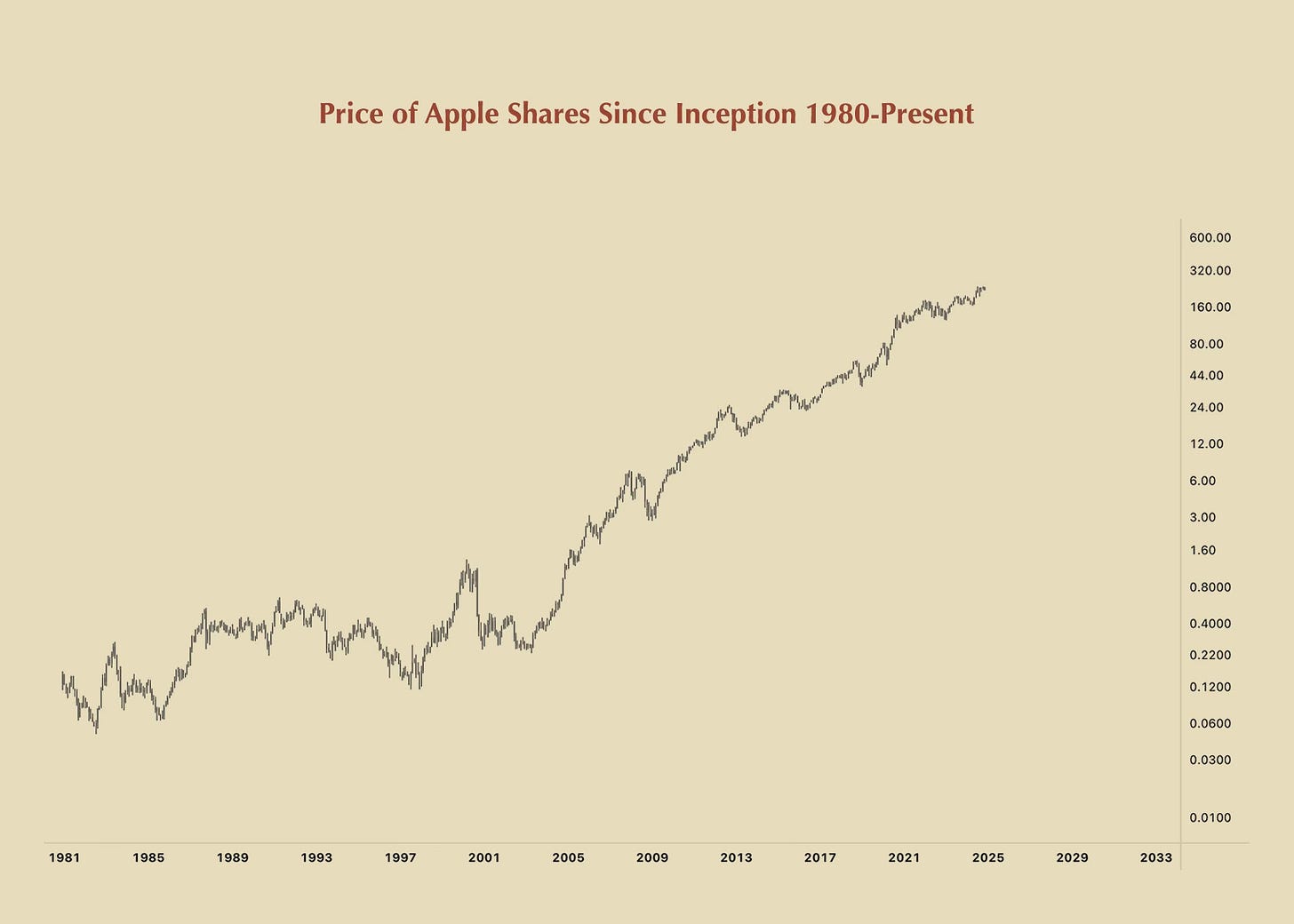

The data series (chart above) represents the price of Apple shares. It starts in December 1980, when Apple was listed as a public company. The opening price, after all the stock splits and adjustments over the years, was around $0.12 (the original IPO price in 1980 was $22). Today, as of the writing of this piece, the price is $234. This is a 1863x appreciation.

Ups and Downs

Had someone invested $1,000 in AAPL shares in 1980, their value, not including dividends, today would be $1.8 million. Holding onto shares for 44 years is not for most people. The primary individuals that do retain ownership of a company for extended periods are the employees themselves.

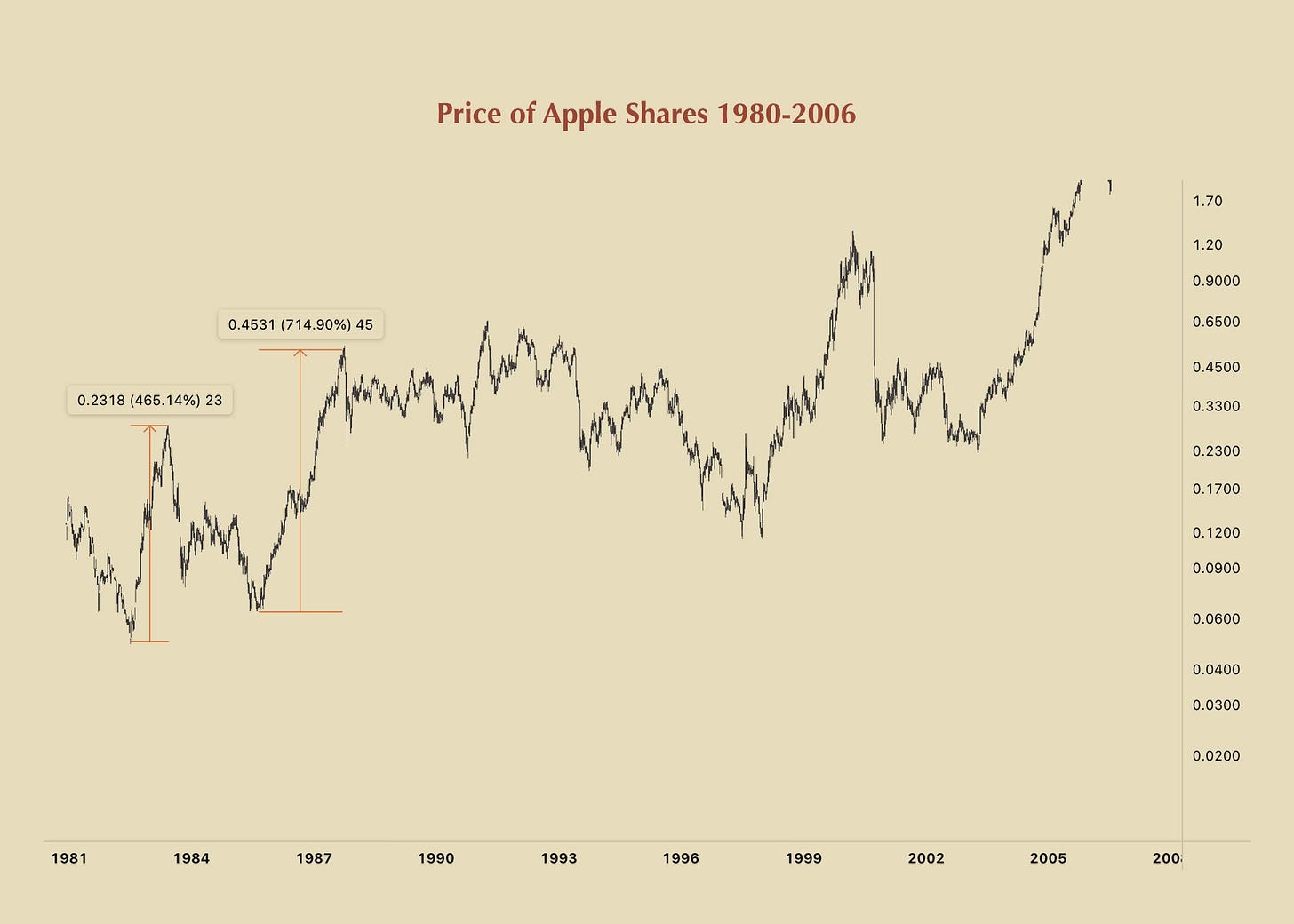

However, if we look a little closer, we see that the majority of Apple’s growth happened from 2003 onwards. In fact, in December 1997, 17 years after their inception on the stock market, and the time when co-founder Steve Jobs returned to the company, the price was the same as it was on day one. There were two periods of exceptional growth in 1982-83 and again in 1985-87, and that was about it (chart below).

Imagine you’re looking at this company in 1997.

It’s gone nowhere for 17 years, while other competing businesses like Microsoft and Dell were flying high. It’s long lost founder, Steve Jobs, comes back into the picture. A man whose follow-on business, NeXT, hadn’t really left much of a dent in the industry over the past 12 years, and who had found renewed success by investing in a film animation studio, Pixar, far removed from the world of producing computer products.

Would you invest your hard-earned money as an investor or time and energy as an employee? Well, this story has been told, and those that did, did well.

Even the greatest of things do take time to flourish. Apple is the most valuable company in the world today, yet for the first half of its life as a public business, the stock price went nowhere. The real growth of the share price began when the company appeared to be on the verge of collapse in 1997. This impending collapse also happened to prompt some meaningful reflection and the implementation of subsequent changes (i.e., re-hiring of Steve Jobs as CEO, a symbolic deal with longtime nemesis Microsoft, the slashing of much of its core product-line, and others), which would certainly have been wildly counterintuitive at the time, both viscerally and logically.

Investing in Life

How does Livermore’s advice about “sitting tight” come to be relevant with the Apple experience we just looked at? Clearly, holding on for the first 17 years of the business from 1980-1997 would have meant a lot of volatility, for little reward. And just as clearly, investing in Apple at its arguably toughest time in 1997, and staying on board ever since, would have been one of the greatest generational investments ever made.

Life is much like this, though, is it not? There will be false starts. There will be traps of exuberance - where we believe we’ve hit the jackpot - and daunting moments of exasperation - where nothing seems to work. Eventually, an opportunity will come along where the foundation is solid, so solid at the core, that even though there may be a myriad issues at the surface, soon enough the trend starts to tend upward. And here, Livermore writes we come to the main challenge:

“The reason is that a man may see straight and clearly and yet become impatient or doubtful when the market takes its time about doing as he figured it must do.” After the experience of so many false starts and rollercoaster rides, our visceral response is to jump off the train far too early when we (finally) find the right one:

“The market does not beat them. They beat themselves, because though they have brains they cannot sit tight.”Self-Sabotage on a Psychological Level

What this is really alluding to on a deeper level is an ingrained pattern for self-sabotage. Whether from our biological disposition, from personal lived experiences throughout our life, or a combination of both, our system has found a perverse kind of equilibrium in “the rollercoaster ride”, and subconsciously seeks it out.

In order for us to grow, we must be open and receptive to expand as an individual. If we find ourselves on a new train ride that is going to mean a lot of growth, our resistance to this is fundamentally a resistance to expand. We sabotage ourselves, by not sitting tight on the train and doing what has to be done to grow and adapt into this new environment. Since such an effort is necessary, not making it is a subtle choice for the rollercoaster ride back down off the train.

There is also something further that often tends to happen concurrently on a psychological level during this process of opting to not sit tight.

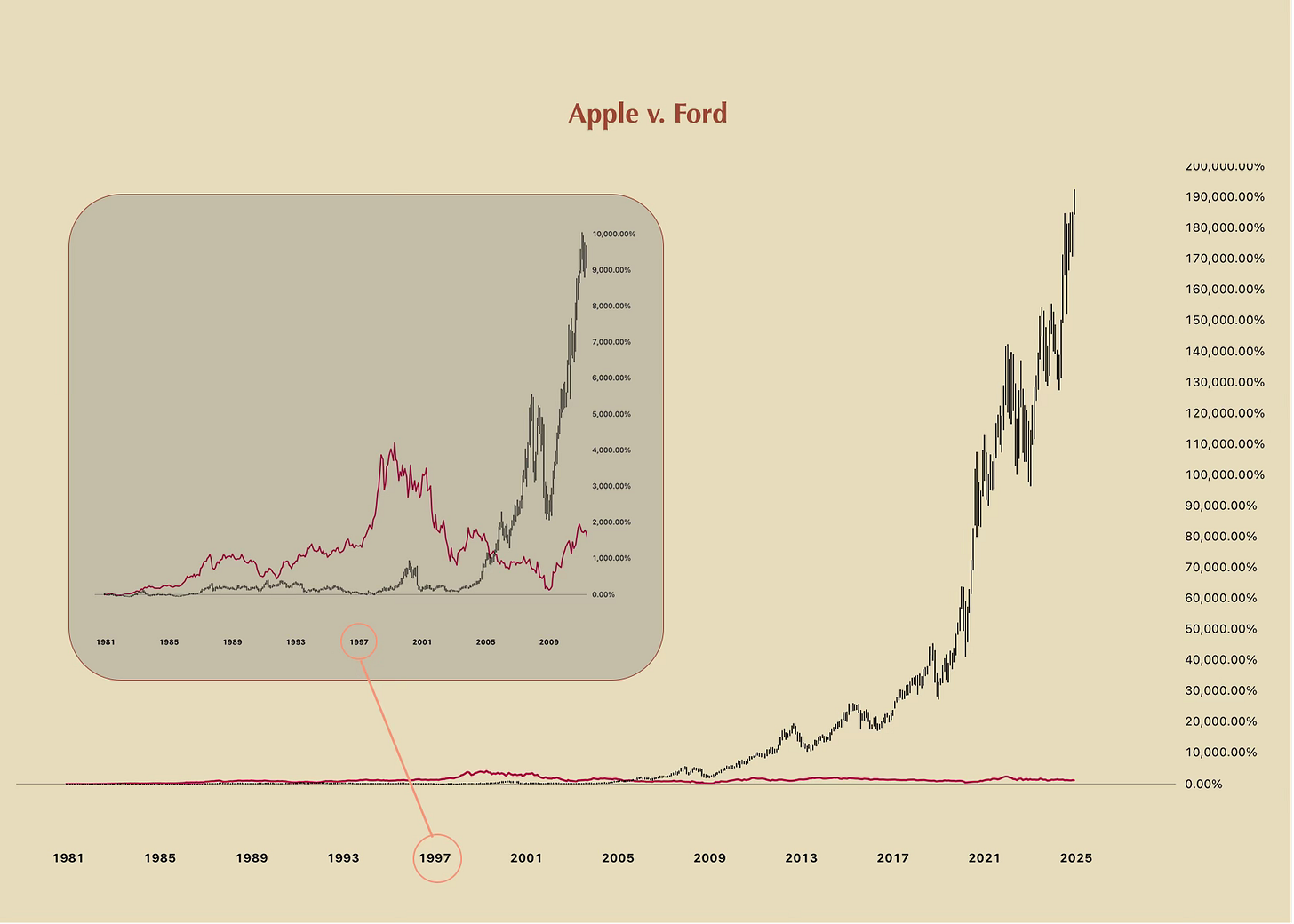

We tend to lower our standards for quality. Prior to all those rollercoaster ups and downs, we may have been internally seeking a high growth opportunity in the person we share our lives with, the career we envision, or the place we settle down to build our lives in. Thereafter, though, and ironically, as it so often happens, just at the most inopportune time, we decide to set our sights on something less challenging and with lower upside, yet “that still, kind of, works.” Less growth potential inherently means more of the same, more often. Our life and psychological state of mind literally become more flat. We literally become grounded in the past, at the expense of the future. Take a look at a comparison of Apple and Ford Motors stock prices in the chart below. Ford was a generational company in the United States, until the new wave came along, and Apple was part of that new wave. Less understood, yet bursting with potential.

Now, it is important not to confuse this analogy with an intentional change in values. For instance, moving from New York City to a sleepy town somewhere in Arkansas on its own is a choice for a flatter life. However, that may also be due to the individuals decision to realign much of their available energy toward something new, like raising a child. So, while the aspects of their life related to the place of living will flatten out or regress, the person may tend to still realise a sense of fulfilment and growth, provided they keep their energy focused in a healthy manner on the growth of the child.

Making Good Choices: Finding the Next Apple in Our Lives

Say we’ve accepted this timeless piece of wisdom from Jesse Livermore and have resolved to sit with and commit effort toward the major investments we will make in our life, even after many prior disappointments. We have decided to develop our self-awareness, and in the process, make the time to keep our attention on any resistance we may be putting up, and any responsibility we are avoiding taking on board which might thwart progress. We become open to wage a kind of internal warfare with ourselves, and do so proactively, so as to give this new opportunity the best chance of a good life. There may still remain the pressing question: “how will I know if this one is the real deal, or just another false start?”

Imagine you’ve just met someone new. Can you project, then and there, what your lives will look like together 5-10 years from now? Can you imagine what you will look like - your values, your passion, your health - 5-10 years on? What about the values and commitments of the other person?

Quite frankly, you really won’t know for sure. Life is non-linear and far too unpredictable on a consistent basis. A degree of common sense helps. And over time with enough reflection and willingness to learn and grow, we do expand our understanding of both ourselves and the world around us. And this helps some more. We start to notice patterns that seem to work well, at least some of the time. Perhaps we’ve picked up on some of those timeless threads, they begin weaving themselves into our minds, and we become more capable to select for a harmony between our inner world and the world out there. Nonetheless, we just can’t predict how amazing things might be when growth takes on a life of its own, and we just can’t accurately envision all the challenges that will come our way.

There are situations where we do have a feeling inside, you might grant that, though. And there may also be those rare situations where we do have a feeling inside and our understanding of the outside world points to something with a strong foundational core to build upon. When these click, will you have the courage to commit, and stay committed? To sit tight.

Amazingly Rare Comes Around Every So Often

The Apples of this world are rare. Yet, there are many, many other positive stories of investments in companies, in marriages, in friendships, in places to live, in vocations and passions beyond work, in the big decisions of our lives. It is quite true that throughout our lifetimes we will all come across, perhaps on no more than a handful or two of occasions, our own version of something or someone special where the space is open for us to commit our energy in a meaningful way.

At this point, we go on another psychological interlude to make what may be a counterintuitive observation: when we do have the courage to commit to one of these amazingly rare experiences in our lives, that experience will change and evolve over the course of time. The recency bias of the mind, its incredible capacity to adapt to new circumstances on demand, will in haste lose sight of the special reasons that forged the experience in the first place, and tend to shift its focus on what’s now in front of us. Yet, those special reasons are at the core of what sustains whatever we have, and provided it is still in place, must be nurtured and given the light of day, and often. Because even as you evolve and go through the spectrum of both exciting and dreadful new periods along that journey, they are as a by-product of that foundation forged in the early days. Take a moment to reflect on your own life experiences in this context. Perhaps you moved to a new country with dreams of the opportunity of a new life or met a new romantic partner who came into your orbit with personality traits you had been imagining for some time. How did the experience evolve? When the exuberance was overflowing, did you keep seeking more and more, or, did you make the time to appreciate how far you’ve come and solidify what you have? When the challenging moments began to weigh you down, did you reflect and fight to adapt and grow, or, did you gradually look for more and more reasons to commit less and less energy?

And here, we come back to Livermore’s piece of wisdom about investing in anything:

“He had not only the courage of his convictions but the intelligent patience to sit tight.” We will all come upon beautiful relationships, special opportunities and experiences at certain junctures in our lives. Can we spot when the opportunity comes along, commit wholeheartedly, and then provide it the care it deserves and do so consistently well? According to Livermore, the real wealth comes to us when we master this.

All of this may be aptly summed up by an analogy of the garments we wear. Fashion has become a questionably superficial domain these days, yet an investment in a high quality piece of lovingly well-made, lovingly well-looked after garment may last you a lifetime. It is timeless. And once we learn how to take care of it well, it makes the experience of life simultaneously more effortless and meaningful. We don’t really need to look elsewhere too much, too often, and can savour more time and energy on what’s most important.

Interesting reading 👍